We all know our athletic wear is supposed to support our performance, not sabotage our health. But what if the very clothes you sweat, stretch, and squat in are laced with toxic chemicals linked to cancer, hormone disruption, infertility, and more? Welcome to the uncomfortable truth behind performance gear and “forever chemicals” — a phrase that sounds like it belongs in a bad sci-fi novel, but is instead lurking in your favorite leggings.

In this deep dive, we’re going to peel back the layers (literally) of PFAS in athletic clothing — how they got there, what they’re doing to your body, and why this isn’t just another greenwashing scandal but a serious health and environmental concern. Athletes deserve better than marketing spin and chemical cocktails in their compression wear.

Let’s stretch into it.

What Are PFAS, and Why Are They in Your Clothing?

PFAS — short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances — are a group of nearly 9,000 synthetic compounds known for their grease-proof, water-resistant, and stain-repellent properties. That’s why they’ve been a darling of the textile and cookware industries since the 1940s. Think Teflon, Scotchgard, and yes, waterproof jackets and breathable sports bras.

The trouble? These compounds don’t break down. Not in your body, not in the environment. Hence the nickname: “forever chemicals”.

How PFAS Sneak Into Activewear

PFAS end up in clothing primarily through:

Surface treatments to repel water, oil, and stains

Membrane layers in outerwear for breathable waterproofing (e.g., Gore-Tex)

Contamination from equipment, recycled textiles, or shared factory space

Residuals in water used during manufacturing

Even if a company doesn’t intentionally add PFAS, the supply chain often ensures these chemicals show up uninvited — like glitter after a kid’s birthday party.

Toxic Gear: The PFAS Problem in Popular Athletic Brands

Recent independent testing commissioned by Mamavation and Environmental Health News found that:

Over two-thirds of sports bras and 25% of leggings from brands like Lululemon, Athleta, Gap, Under Armour, and Adidas tested positive for fluorine — a marker for PFAS.

In many cases, the highest concentrations were in skin-contact areas, such as the nipple zone in sports bras and the crotch region in leggings. Not exactly where you want hormone disruptors hanging out.

While some PFAS exposure could be accidental, experts suspect purposeful use in moisture-wicking or antimicrobial sections of garments.

Greenwashing and Lawsuits

The contradictions are hard to ignore. Many of these same brands promote their products as “sustainable,” “non-toxic,” or “safe for sensitive skin” — while quietly lacing them with fluorinated chemicals.

In fact:

Thinx, a popular period underwear brand, settled a $5 million lawsuit over PFAS contamination.

REI faces ongoing legal action for PFAS-laced raincoats.

Patagonia, L.L. Bean, and W.L. Gore (Gore-Tex) are pledging to phase out PFAS, but testing has still found banned chemicals in their products.

Health Effects of PFAS: Not Just a Cosmetic Concern

The issue isn’t just that PFAS exist in athletic clothes — it’s what they do once they make contact with your body. Studies from the National Academies of Sciences have linked PFAS exposure to:

Certain cancers (kidney, testicular)

Thyroid dysfunction

Immune suppression and reduced vaccine efficacy

Hormonal disruption and infertility

High cholesterol

Low birth weight

Your skin isn’t meant to be a hazmat suit.

Can PFAS Absorb Through Skin?

Good question. While ingestion remains the most studied route (through drinking water, for instance), there’s growing evidence that dermal absorption is a concern — especially with prolonged skin contact and sweat-increasing permeability.

Studies have found PFAS in skin oils and sweat, suggesting transfer from fabrics. And with high-friction, tight-fitting clothing worn for hours, athletes may be especially vulnerable.

Think about it: you wouldn’t drink a chemical-laced smoothie post-workout. Why wear it?

PFAS in Smartwatches: Lawsuits, Fluoroelastomers, and Athlete Exposure

Wearable fitness tech has become nearly ubiquitous among athletes, with smartwatches and fitness trackers marketed as tools to improve health, optimize performance, and enhance well-being. But recent investigations have revealed a disturbing contradiction: many smartwatch wristbands may contain high levels of PFAS, particularly in bands made with fluoroelastomers—a synthetic rubber prized for its sweat resistance and durability.

A 2024 study from the University of Notre Dame tested 22 popular smartwatch and fitness tracker bands and found detectable PFAS in 15 of them, with total fluorine concentrations exceeding 1% in several cases. The most commonly found compound, PFHxA (perfluorohexanoic acid), is linked to liver damage and is currently under scrutiny by EU regulators. Even PFOA, one of the most hazardous legacy PFAS, was detected in certain bands.

This issue has moved beyond the lab and into the courtroom. In January 2025, Apple Inc. was hit with a proposed class action lawsuit alleging that its Sport Band, Nike Sport Band, and Ocean Band were falsely advertised as health-promoting and environmentally sustainable — while actually containing dangerous levels of “forever chemicals.” The suit cites not only misleading marketing, but also the fact that prolonged skin contact, sweat, and heat — common during workouts — amplify dermal absorption of PFAS.

These findings mirror broader concerns about wearable PFAS exposure, particularly for athletes who wear their devices daily and during intense training sessions. With both scientific scrutiny and legal pressure mounting, this issue underscores the urgent need for transparency in wearable tech materials and a shift toward safer, PFAS-free alternatives.

Environmental Fallout: The Toxic Trail from Factory to Landfill

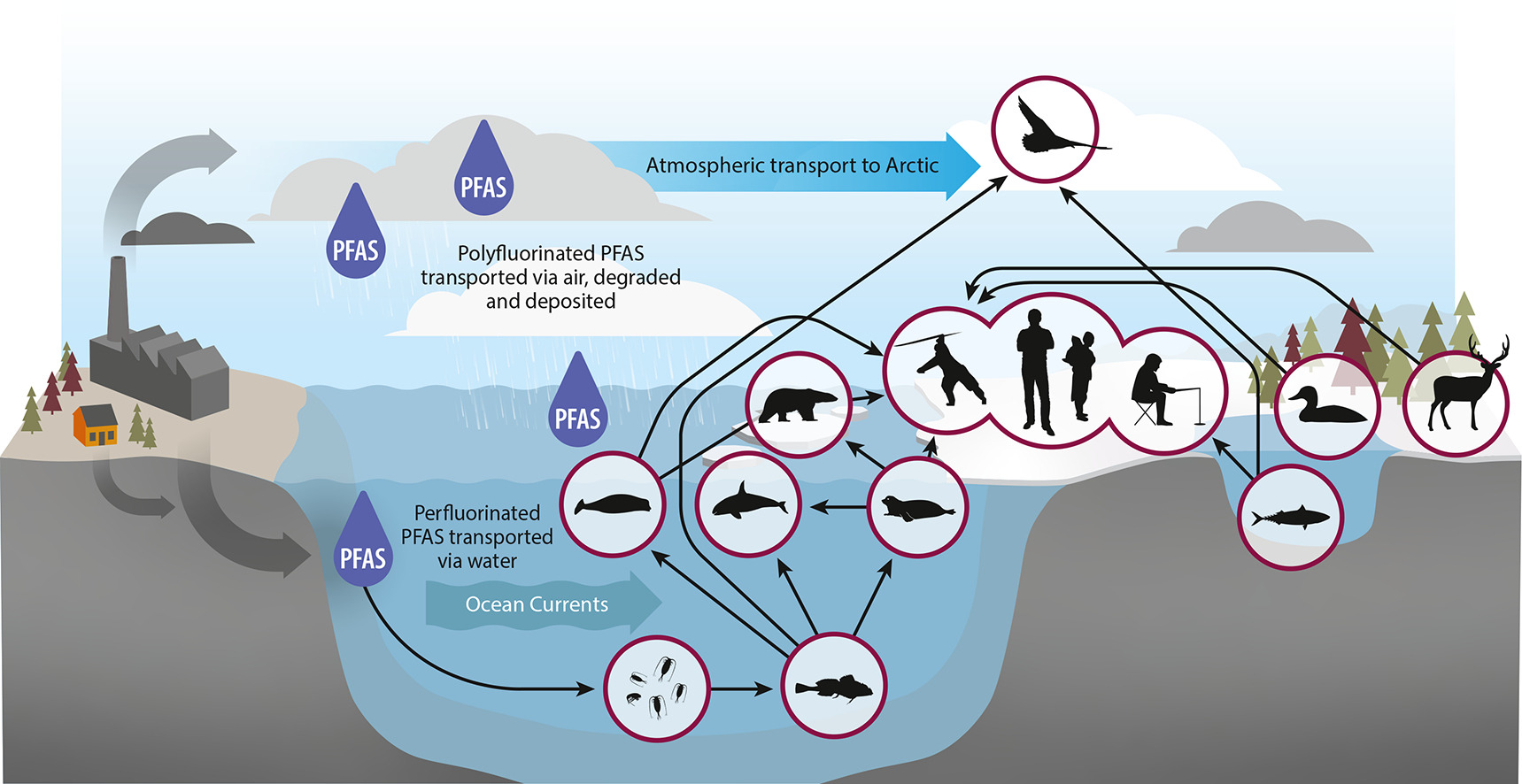

From production to disposal, PFAS create a chain of environmental destruction:

Textile mills are PFAS “hot spots” contaminating air and water

Wastewater treatment plants can’t filter them out — so they enter rivers and oceans

Clothing sheds PFAS into laundry water and indoor dust

Landfills leach these compounds into groundwater

Incineration doesn’t neutralize PFAS — it spreads them into the atmosphere

It’s not just your skin at risk. It’s your community’s water, your kid’s school uniform, and the fish on your dinner plate.

PFAS Are in Everyone

The CDC has found PFAS in the blood of nearly every American tested. Breast milk studies show alarming levels of newer short-chain PFAS compounds. Even polar bears have tested positive.

Forever chemicals have gone global. Athletic clothing is a silent contributor.

Microplastics and Polyester: The Other Toxic Tagalong

PFAS aren’t the only hitchhikers in your gym bag. Nearly all synthetic athletic apparel is made from polyester, nylon, or spandex — plastic-based fabrics that shed microplastics with every wash, wear, and stretch. And just like PFAS, microplastics don’t just disappear. They enter our water, our food, our lungs, and yes, even our bloodstream.

Studies have shown that:

A single load of synthetic laundry can release up to 700,000 microplastic fibers.

These fibers escape even modern wastewater treatment plants and wind up in oceans, rivers, and eventually seafood.

Microplastics have been detected in human placenta, lung tissue, testicles, brain tissue, and blood — which should make you think twice before calling your moisture-wicking tee “breathable.”

Polyester’s Dirty Secret

Polyester is cheap, durable, and stretch-friendly — everything a fitness brand wants. But it’s also:

Made from petroleum

Non-biodegradable — it will outlive you, your kids, and your grandkids

Often combined with chemical dyes and finishing agents (including PFAS), creating a chemical soup of endocrine disruptors

And while it may be marketed as “recycled,” most recycled polyester still sheds fibers. It’s not a free pass — it’s a slightly less terrible one.

The Problem with “PFAS-Free” Labels

“PFAS-free” isn’t regulated. Companies may still use:

Short-chain PFAS — which are harder to detect but potentially just as harmful

Trade-secret blends — which escape testing

Contaminated recycled materials — unintentionally reintroducing PFAS

Since the label game is murky, what’s your best bet? Choose brands with strict third-party certifications (like GOTS or OEKO-TEX) that go beyond disingenuous claims.

Legislation and the Push for Reform

Momentum is building at the legal level:

New York banned the sale of PFAS-laced garments by the end of 2023.

California restricts PFAS in clothing by 2025 (excluding extreme weather gear until 2028).

Maine plans a full PFAS ban for all products by 2030.

Washington will restrict PFAS in textiles and home goods by 2025.

With large states leading the charge, the industry is being forced to pivot nationwide.

What the EPA Is Doing

The EPA has finally stepped in to regulate PFOA and PFOS, classifying them as hazardous substances. But these are just two of thousands of compounds. The industry has already pivoted to using newer, unregulated PFAS — many of which are now showing up in breast milk, blood, and wastewater.

Until there’s a comprehensive ban on all non-essential PFAS, the loopholes remain wide enough to drive a Lululemon delivery truck through.

What Athletes and Consumers Can Do

Let’s be real: PFAS exposure is practically unavoidable today. But that doesn’t mean you’re powerless.

Here’s how you can lower your exposure:

Check your labels — Avoid items labeled water- or stain-resistant unless certified PFAS-free.

Skip the Scotchgard — Resist the urge to DIY waterproof your clothes.

Support transparent brands — Look for companies disclosing all chemicals and using PFAS-free certification.

Buy less, buy better — High-quality natural fibers (like organic cotton or Merino wool) don’t need chemical shields.

Wash smart — Use a microfiber-catching filter and avoid excessive heat, which can degrade coatings.

Advocate — Ask your favorite brands about PFAS and demand clarity.

Athletes for Awareness

Whether you’re a pro fighter, yogi, trail runner, or dad hitting the gym after work, your clothing shouldn’t be a health risk. We often scrutinize our supplements and hydration routines — but the same level of awareness needs to go into what we wear.

Your skin is your largest organ. It’s not a wetsuit. It’s time athletic apparel reflects the health values of the people wearing it.

Conclusion: The Future of Fitness Fashion

The PFAS issue in athletic clothing is a case study in how performance, convenience, and profit have outpaced precaution. But as legislation tightens and consumer awareness grows, there’s hope for a new generation of truly clean gear.

Let’s not settle for performance at the cost of our endocrine systems. Let’s demand innovation without contamination. Because in the end, if your yoga pants are quietly dosing you with carcinogens… are you really living your best life?

It’s time to put pressure on the apparel industry — not just through our workouts, but with our wallets.